Fall 2014 – Just Teach One, no. 5

Prepared by Duncan Faherty (Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center) and Ed White (Tulane University)

Text and Introduction (PDF) | Text (XML File using TEI encoding)

Introduction

The author of Humanity in Algiers in unknown, but it may be possible to extrapolate from the novella’s printer, Robert Moffitt, active in the Troy, New York region from 1796 until his death in 1807. While Moffitt’s primary publishing venture appears to have been the successful regional newspaper The Northern Budget, he also published (first under his sole name, later with Zebulon Lyon, then with Oliver Lyon) a number of Baptist writings. These included the Minutes of the Shaftsbury Baptist Association (from 1800 to 1806), the records of a large consortium of churches in the area where New York, Massachusetts, and Vermont intersect; Matthew Adgate’s A Northern Light; or A New Index to the Bible (1800); the narrative of the travels of Baptist missionary Lemuel Covell (1804); the hymns of Joshua Smith and Samson Occom (1803); Cornelius Jones’s History of Baptism (1801); and a medically-oriented study of electricity with strong theological inflections. Humanity in Algiers appeared in 1801 in that denominational context, and its subscribers’ list was drawn from many communities in the Shaftsbury Baptist Association region. (Among these subscribers was the prominent African-American minister Lemuel Haynes, active in the Rutland, Vermont, area.)

It appears, too, that the political orientation of this reading community was “Republican,” emerging from New York’s antifederalists (among whom Matthew Adgate was prominent) and linked with the national Democratic-Republican party of Thomas Jefferson: within New York state politics, Moffitt appears to have been aligned with a broadly democratizing trend among upstate New York farmers against the concentration of mercantile and banking power in New York City. We might also speculate that this reading community was somewhat local. We have been unable to find advertisements for the novel outside of the region of the Shaftsbury Baptist Association, and copies were still on sale in Rutland, Vermont in 1805 and in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1811, apparently from the original Troy printing. As with many publications of this time, copies may not have circulated far out of the region, or perhaps outside of the cultural community.1

Keeping the scope of the novella’s audience in mind helps us think about its possible significance in the growing abolition movement. In 1794, a Philadelphia convention tried to bring together delegates from a number of abolition societies. Its small size and narrow reach aside, the aspiration for a national-level movement—and political solution—was clear, though practical advances were largely won at the state and local levels. Many abolition groups had a denominational orientation, meaning that abolitionist arguments were couched in spiritual and theological terms and often linked with institutional practices and pressures. In addition, they were typically gradualist in orientation, arguing for the long-term, phasing out of slavery to minimize its economic impact upon slave-owners. In Humanity, the character of Omri (who is given perhaps the most Hebraic name) seems to demonstrate these tendencies, developing a rhetorical strategy to argue for manumission within his social community.

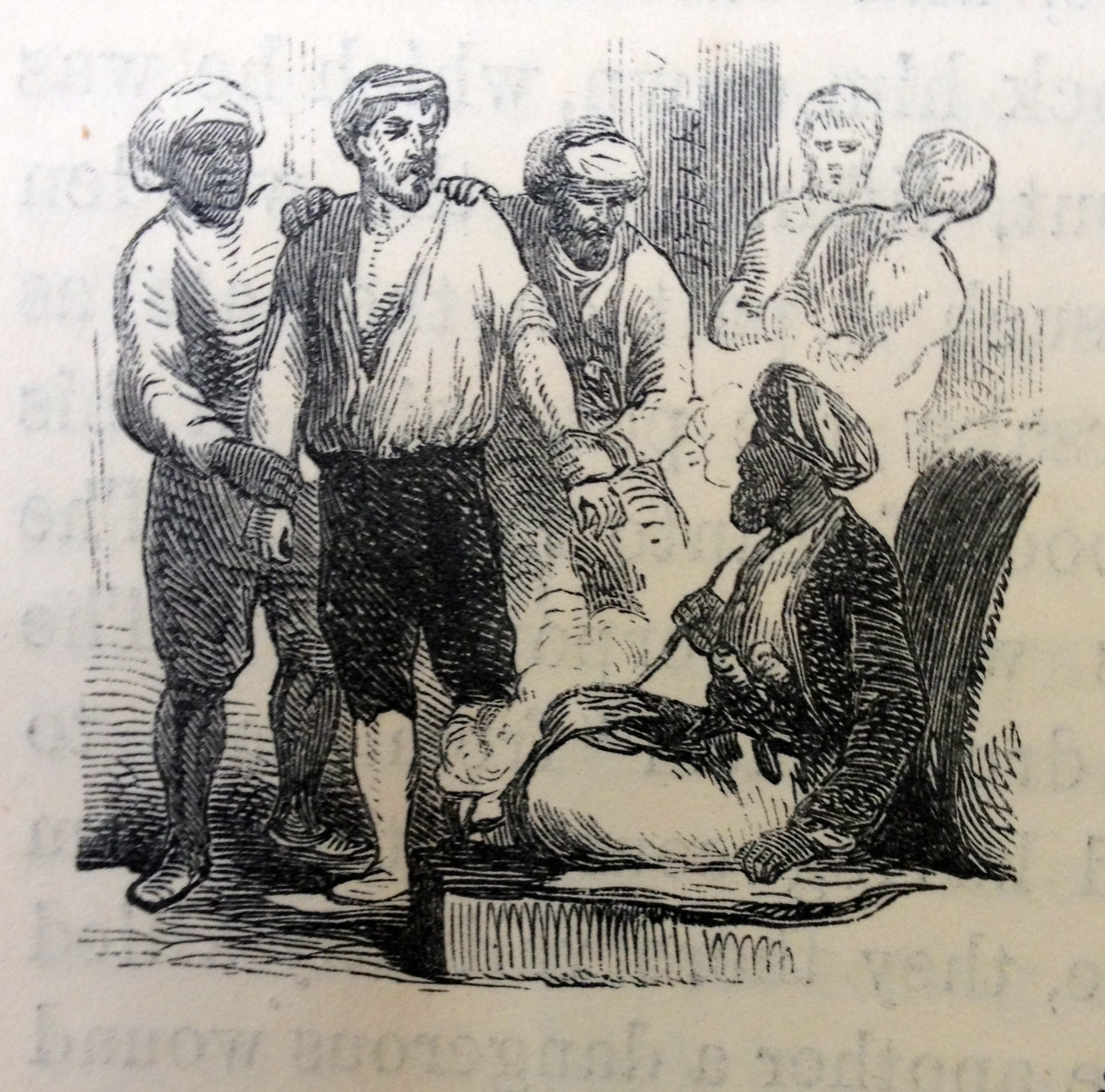

At the same time, three important trends converged around the Algerian (“Algerine”) setting. First, Algiers was notorious as the primary North African site of slavery for white North Americans. Thousands of sailors, generally Europeans and North Americans, experienced slavery in Islamic coastal sovereignties in the southern Mediterranean, with several publishing popular captivity narratives: these have come to be known as Barbary captivity narrative after the Barbary (or Berber) coast of northern Africa. This captivity phenomenon allowed abolitionists to imagine African slavery in reverse: whites unjustly kidnapped, torn from families, to languish in servitude. At the same time, this adversarial contact with Algiers and other Muslim states meant that Algerians sometimes figured as compelling cultural Others looking at the new United States. In 1787, Peter Markoe, for example, had published an account of the United States from the point-of-view of an “Algerine Spy in Pennsylvania.” Finally, a growing body of ethnographic literature was appearing describing African societies as complex, historically rich cultures. If these works often paved the way for European imperialists, they were also counter-deployed by abolitionists in works like (most famously) Anthony Benezet’s That Part of Africa Inhabited by the Negroes, and the Manner by Which the Slave-Trade is Carried On (1762, and frequently cited and reprinted). As a result, a literature about slavery began to appear drawing variously on these tendencies. In 1790, for example, Benjamin Franklin published an ironic defense of the enslavement of Christians in the voice of a Sidi Mehemet Ibrahim, “a member of the Divan of Algiers.” And 1797 saw the publication of the abolitionist poem “The American in Algiers, or the Patriot of Seventy-Six in Captivity” as well as Royall Tyler’s The Algerine Captive, a two-volume novel exploring white enslavement. Humanity in Algiers marked a slightly later attempt to imagine the dynamics of abolition within a foreign context, and interestingly without the usual anti-Islamic rhetoric of many discussions.

Endnote

1 The tri-state area was relatively populous though. For example, while Troy’s 1800 population was around 5000 people, significantly less than major coastal cities like New York (~60,500), Philadelphia (~41,000), Baltimore (~26,500), or Boston (~25,000), it was nonetheless on a par with cities like Albany, Savannah, Richmond, New Haven, and New London (all cities of 4500 to 6000 people).

Suggestions for further reading

Perhaps the first critic to take note of Humanity in Algiers was Henri Petter, who described it as a tale “designed to illustrate the hardships endured by slaves, whether Americans in Algiers or Negroes in the United States”; see, Petter, The Early American Novel (Ohio State University Press, 1971), 294. James R. Lewis briefly mentions Humanity, in conjunction with Royal Tyler’s The Algerine Captive, as deploying a narrative “strategy of using Barbary slavery to condemn North American slavery”; see Lewis, “Savages of the Seas: Barbary Captivity Tales and Images of Muslims in the Early Republic,” Journal of American Culture 13:2 (1990), 83. Robert Allison groups Humanity among a number of Barbary captivity themed antislavery tracts, and concludes that that the novel “offered Americans a choice in redeeming their souls and nation”; see, Allison, The Crescent Obscured: The United States and the Muslim World, 1776-1815 (Oxford University Press, 1995), 95. Anouar Majid reads Humanity as an autobiographical account of captivity, suggesting that the narrative exposes the “hypocrisy and double standards” of the U.S. in regards to slavery by presenting “a remarkable twist of fate, a benevolent black African [who] helps a white American regain his freedom”; see Majid, Freedom and Orthodoxy: Islam and Difference in the Post-Andalusian Age (Stanford University Press, 2004), 97. Timothy Marr considers how Humanity mimics the tropes of the oriental tale in order to present a “view of Islam as a potentially benevolent system of morality”; see Marr, The Cultural Roots of American Islamicism (Cambridge University Press, 2006), 145. Hester Blum ranks Humanity alongside a number of other early nineteenth century literary works which imitate the language of captivity narratives written by sailors to underscore “the hypocrisy of white Americans” in condemning white slavery in North Africa while continuing to profit from the enslavement of black Africans in the U.S.; see Blum, The View from the Masthead: Maritime Imagination and Antebellum American Sea Narratives (University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 56.

For more information about Barbary Captivity more generally see, Paul Baepler, “The Barbary Captivity Narrative in American Culture,” Early American Literature, 39.2 (2004), 217 For more information about religious publishing and reform movements see, David Paul Nord, “Benevolent Books: Printing, Religion, and Reform,” in A History of the Book in America, Volume 2: An Extensive Republic: Print, Culture, and Society in the New Nation, 1790-1840 (University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 221-246.

Teaching Reflections

The following are responses written by participants who have included this text in their teachings.

- Melissa Gniadek – Negotiating Expectations

- Jordan Alexander Stein – Pairings

- Marty Roja – Rewarding Passivity

- Laura M. Stevens – “The Problem of Sympathy” or “Teaching to Teach”

- Michael Drexler – Among Slave Narratives

- Melissa Adams-Campbell – Global Perspectives on Captivity and Slavery

- Kelly Wisecup – Global Perspectives on Captivity and Slavery

- Drew Newman – Canonicity and Memory

- Andy Doolen – Frontiers of the 19C

- Matthew Duques – Gendered Abolition

- Jon Blandford – Making Literary History: Just Teaching One in an Undergraduate Survey Course

- Karen Salt – Caribbean Inflections